In the 1940s, Toyota began matching inventory with demand in order to allow for a “just-in-time” provisioning and production process. They did this by implementing a visual system for monitoring the flow of parts from the supplier, to storage facilities, to the assembly line. This system reduced costs, improved quality, and sped up the rate of production.

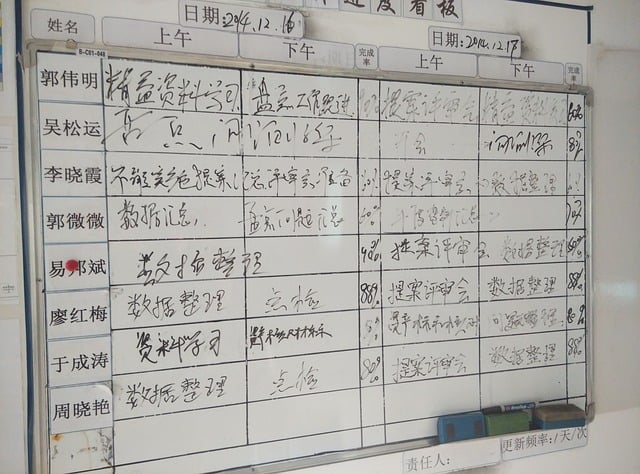

They called this process “Kanban,”’ a Japanese term that literally translates to “signboard” or “visual signal.” This approach was found to be effective, and so “Kanban Cards” began to spread to manufacturing companies across the globe to help control the production and purchasing of parts. Today, the core principles of Kanban - as defined by David J. Anderson, Jim Benson, and others - are effectively leveraged by workers in a variety of industries, not just manufacturing.

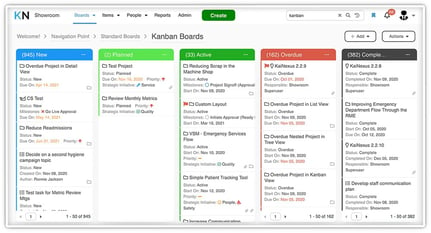

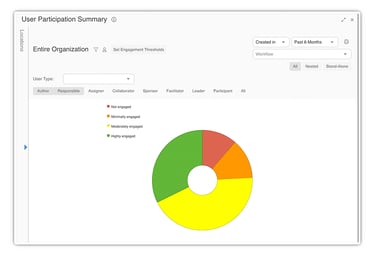

As the name’s origin suggests, one of the key components to Kanban is visualization. When using Kanban to manage work, for example in software development or construction team, it’s important to visualize the work tasks that need to be done, either on post-it notes or in software. This allows all parties to observe the flow of work, which in turn allows opportunities for improvement - such as blockers, bottlenecks, and queues - to become clear. Visualization is not a one-time practice at the start of Kanban, but continues after its implementation, serving as a means of communication about the state of projects, processes, and the inventory of work that remains to be done.

The ultimate goal of Kanban is to move each piece of work efficiently from beginning to end without waste or lag. Work moves from one stage to the next only when demand - from an external customer or the next stage - makes space for it. For this to be accomplished, the amount of work in the pipeline must be limited to what can reasonably be managed at any given time. Because work is never forced forward against the pull of demand, we avoid piling too much work on a person, which causes stress and impedes flow.

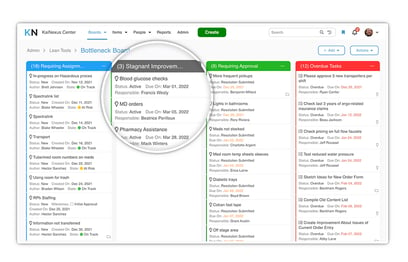

If the first two principles have been put in place, work will flow freely. Therefore, attention should be directed to any interruptions inflow. Such inefficiencies represent opportunities for further visualization and for improvement.

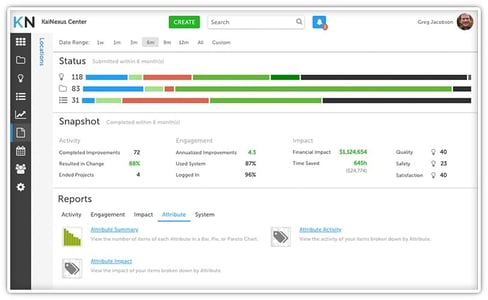

Since conditions, resources, and customer demands develop over time, it’s clear that this approach demands constant monitoring and analysis to assess flow and look for opportunities for improvement.

If a workflow is visualized and work in progress is limited, any interruption inflow can be identified, targeted, and resolved before a backlog forms or grows too large. This is important in any industry, as backlogs tie up investment, create prioritization conflicts, and increase the distance to customer value.

Additionally, team effectiveness can be measured by tracking flow, production pace, and quality, allowing any teams that need it to be identified for further coaching. While it is simple, the Kanban approach enables teams to operate more efficiently, while reducing friction and maintaining a flow of value to customers.

When practicing Kanban, you may encounter several opportunities for improvement. If you put off recording those insights until you are near some physical Kanban board or until your team’s next meeting, you might forget your idea. Accessing continuous improvement software on a mobile device allows you to enter those ideas as they occur to you, preventing this loss of information.

When you’re using Kanban, you’re engaging employees, making them think about their workflow and opportunities for improvement, not only for their individual parts of the project, but for the process as a whole. That engagement shouldn’t stop once you go back to your office. Building a virtual team in a continuous improvement software platform around each ideas promotes cross functional collaboration in formulating and implementing a plan for improvement and promotes greater buy-in.

Copyright © 2026

Privacy Policy